I am not the first rabbi to preach from this bima. Let me tell you who was.

Joseph Stolz, born in Syracuse, New York in 1861, became one of the first rabbis born in the United States.1 He was from a poor family, but he excelled at his local high school; and he had an early calling to the rabbinate. He was ordained in the second class of the Hebrew Union College and then served for three years as an assistant rabbi in Little Rock, Arkansas before coming to Chicago in 1887. Here, he served as the second rabbi of Zion Congregation2 (which is now Oak Park Temple) before founding a new community called Temple Isaiah.

Rabbi Stolz was a devoted student of Isaac Mayer Wise, the father of American Reform Judaism, and the two corresponded throughout his life. Stolz was known to have a pleasant voice, “a flare for oratory and eloquence,”3 and a firm commitment to the principles of Reform Judaism. He was compassionate and forceful, humble and driven, dedicated to service and devoted to the pursuit of justice and truth.

Temple Isaiah’s first edifice was built in 1899 at the corner of 45th Street and Vincennes Avenue and was dedicated to Isaac Mayer Wise. Twenty-five years later, Isaiah merged with the nearby Temple Israel, and the new congregation—Isaiah Israel—moved into this magnificent building, which in many ways stood as the symbolic monument to the Judaism they all believed in.

Joseph Stolz had a vision, and it was a vision that reflected the needs and aspirations of his community. At the very inauguration of Temple Isaiah, on the date of its first service back in January of 1896, Stolz delivered a rousing and inspiring sermon that laid the course for generations to come. I have the text here, written in pencil by his own hand, stored lovingly in our congregation’s archives. He wrote:

Only to magnify religious truth and make it honorable in the eyes of men do we this day join the sisterhood of Jewish congregations that circles the earth; only that more men and women may grow in the knowledge and love of God, walk in His light, learn to do well, seek justice and relieve the oppressed have we added another place of worship to the many that already grace our city.4

Rabbi Stolz was excited to be part of a Jewish revival in Chicago, with a flourishing of new communities and organizations, and he saw Temple Isaiah as central to that movement. He outlined the purpose of the new congregation: “to battle prejudice and intolerance, to defeat oppression and injustice, to stir up the conscience against warfare and every kind of moral obliquity” and ultimately “to magnify religious truth and make it honorable in the eyes of men.”5

To achieve this vision, Stolz and his community established schools for the teaching of boys and girls and welcomed both men and women as full members of the congregation. They participated in legal, educational, and societal reforms of their day while remaining fully committed to the modern observance of ancient practices. Judaism was electric and alive, continuous from generations past while forging a new path for the children and grandchildren that would be raised in these halls.

This is the Judaism enshrined in this sanctuary. This is the Judaism envisioned by Joseph Stolz and our building’s main architect, Alfred Alschuler. These values are literally carved into the walls and painted on the windows. As Rabbi Stolz wrote of this beautiful space:

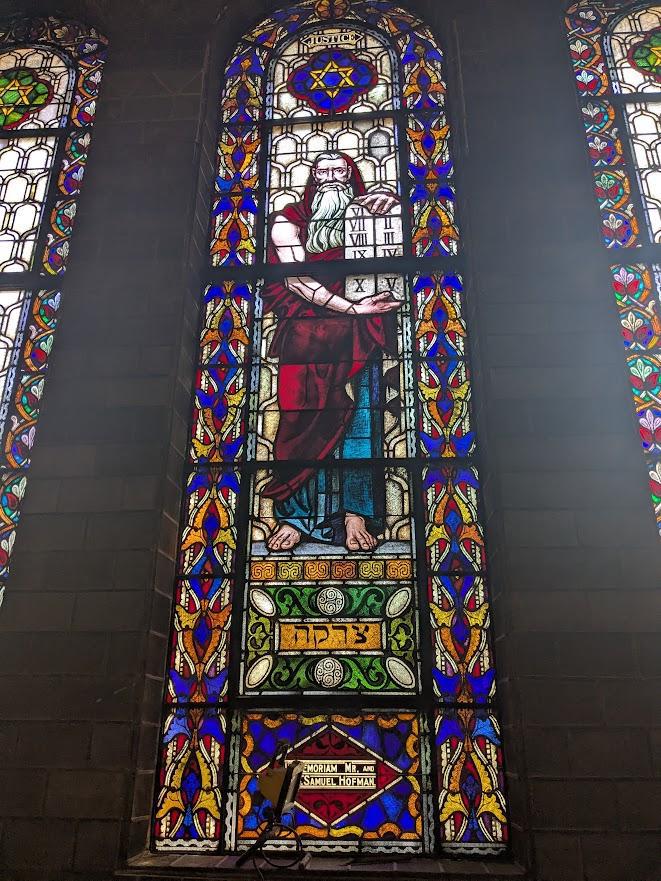

Every single feature of the building has been carefully studied to the minutest detail. … The richly colored art windows bearing the heroic figures of Moses and Isaiah as well as Biblical inscriptions and Jewish religious emblems and symbols, arranged in six groups, remind the worshipper that “the beauty of holiness” expresses itself through the virtues of Justice, Peace, Truth, Holiness, Love and Piety.6

These six values, etched into our stunning stained-glass windows, and the biblical quotes on the walls have inspired our community for a hundred years; and this year, as we return to this beautifully restored house of worship, for the 100th celebration of the High Holy Days in this space, they serve as the inspiration for each of my High Holy Day sermons.

In honor of Rabbi Stolz’s vision, I want to draw our attention first to the most striking images in our windows, those towering figures of Moses and Isaiah. These two figures are paragons of the past and of the future and call us to consider where we stand today at our own crossroads of decision. As the new year dawns, these figures beckon to us once again, inviting us to consider where we’ve come from and where we strive to go.

We look first to Moses.

He represents our past—the past of our people, of course, and also the past of this specific congregation. We might expect the great lawgiver to be connected to Torah or Mitzvot, but our window is inscribed with the word Tzedakah, translated here as “justice.” The past that stands behind our congregation is not an orthodox one. Indeed, even in 1895, Joseph Stolz saw himself as an inheritor of a longstanding Reform Jewish tradition unbeholden to the strictures of orthodoxy. He taught that the Reformers before his generation sought “to modernize the synagogue and to abolish ceremonies,”7 an effort he deemed entirely successful. Judaism no longer needed to be characterized by parochialism and ritual obligation. Reform leaders like Stolz built and strengthened Jewish communities dedicated to what we call tikkun olam, repairing the world, and what they championed as the “high spiritual endeavor”8 of loving justice and righting wrong. This was our congregation’s Judaism 130 years ago, and it is the Judaism represented by the traditional form of Moses. For us, the model of the past is not one of arcane rituals or oppressive morals but rather one of engagement and renewal, of pursuing justice and promoting free thought.

For many of us, perhaps for most, this is the easy part of Judaism, the part which drives us into the street and into the voting booth, which inspires us to open our wallets and to open our homes to those who are in need. As with many traditions, we can follow these patterns almost without thinking, naturally continuing the work of tikkun olam handed to us by our ancestors.

As Joseph Stolz was already teaching 130 years ago, we must stay true to these traditions even as we adapt to new times. “All religious reformations have their roots in the past,” he taught, “and so our Jewish reformers of this century proposed not to break with the past nor to cut away from their brethren. … [Rather,] they were inspired with the truth, the grandeur and the possibilities of Judaism, because they felt the force and the meaning of the 4,000 years of history back of them.”9 We, too, honor our Reform lineage and remain committed to the examples they have set for us generation after generation. Ours is and will always be a congregation dedicated to the welfare of our city, our state, and our nation; ours is a community committed to equality of all who would come to build a meaningful spiritual life here; ours is a place where Judaism can be thoughtfully and joyfully rediscovered and revealed in every age for people of all backgrounds and ages.

With this proud array of traditions behind us, and without abandoning them or turning away, we look also to the future and see something new ahead. And for this, we look to Isaiah as our guide.

Isaiah, perhaps more than any other prophet, is often associated with teachings of social justice and protection of the poor. Yet in our sanctuary, Isaiah is paired with the value Kodesh, translated “Holiness.” So here, where our past is suffused with social responsibility, the challenge of our future lies in revitalizing the “religion” part of the Jewish religion. To be an עַם קָדוֹשׁ , a “holy people” (Deut. 7:6, 14:2, 21), has always been a lofty aspiration. What does it mean today to stand unabashedly for holiness in a society that often casts a suspicious eye at all things “religious”?

An essential first step is to break the unfortunate association between “religious” and “orthodox.” Religiosity is much too broad to belong only to one group. Religion, as we learn from scholars of religion like Rachel Beth Gross, “is best understood as meaningful relationships and the practices, narratives, and emotions that create and support these relationships.”10 These can be relationships among people, relationships between us and our ancestors, or relationships between us and the divine.11 So yes, religion includes rituals like prayer services and holiday observances, but there’s much more to it than that. To be religious can also mean taking seriously the folkways of our people, appreciating the inherent connection among fellow Jews, and sensing with genuine curiosity that a higher power animates the world in which we live. Morality itself, I would argue, is religious; for to assert something is right or wrong I must appeal to some sensibility or authority outside myself. Religion is not only the domain of fundamentalists, and we damage our own moral credibility when we cede “religious ground” to the traditionally observant.

Let’s retire the phrase, “I’m not religious – I’m Reform.” Instead, let’s embrace a robust Reform religiosity—modern and progressive—that connects us to something larger than ourselves and which affords a vote—but not a veto—to the past. This, I believe, is the holiness Isaiah calls us to, a holiness in which we celebrate the distinctions of Jewish practice and belief and insist that the world is better for them being in it.

What might this actually look like?

First, embracing holiness means embracing one another. Our society is facing a pandemic of loneliness; and as I’ve heard so often from many of you, making friends is almost impossible. Our days are filled with work, family obligations, and digital media; and while many of us sense that something is missing from this equation, we never have enough time to fill the gap. What’s missing is community, the once-treasured intermediate level of relationship between those who are very close and those we know only on the surface.

And I’m happy to say that here in this room, and within the metaphorical walls of this congregation, community is there for the taking. Judaism offers us the opportunity to bypass surface-level connections and to feel the strength and reassurance that comes from knowing we belong. It’s not always easy to engage with the Jewish community. It takes time, effort, a little knowledge, and sometimes some money. It also requires going out of our way and, occasionally, breaking our habits. But it’s worth it. I promise. In fact, I’ll make you a money-back guarantee. Sign up for our volunteer-organized brunch club, and I’m confident that you will find the experience meaningful, even joyful. Brochures are in the hall! Eating with people from across the spectrum of our community is a marvelous example of religion in action. And I’m confident Isaiah would agree.

Another aspect of embracing holiness might be exploring Jewish learning and practice. We seek not only meaningful relationships but also a general sense of making meaning of the world we live in. And again, Judaism can help.

The study of ancient texts, engaging in some form of prayer, observing holidays—even the unfamiliar ones—and making choices about kosher food and Shabbat are all potential methods of religious engagement that can help us discover a deeper understanding of our tradition and ourselves. Our congregation is a perfect venue for this spiritual search, and we have a ready-made opportunity for deep and meaningful learning: Our adult b’nai mitzvah program is a wonderful way to get to know fellow congregants, to become more familiar with principles of Jewish thought, and to take firmer hold of Jewish prayer. The program starts in mid-November, information is in your handouts, and I’m very eager to discuss the details with anyone who’s interested.

And finally, one more approach to embracing holiness is to frame our politics, our volunteering, and our work for social justice as distinctly and intentionally Jewish. That is to say, we not only pursue justice, as the Moses on our sanctuary’s window would command us, but we do it in a way that is drawn from, and leads us toward, our religious tradition. When we stand with immigrants because Jews are immigrants; when we fight for public education because Jews are People of the Book; when we demonstrate for the end of war because we are taught בַקֵּשׁ שָׁלוֹם וְרָדְפֵּהוּ , to “seek peace and pursue it” (Psalm 34:14)—these actions reverberate with the power of people and ideas that strengthen resolve and ennoble the soul.

I cannot tell you how often I as a rabbi and we as a congregation are invited to political action not only because of our values—though they are usually in alignment—but because of our religious voice. KAM Isaiah Israel is not the Hyde Park Neighborhood Club. We are not the University of Chicago, nor are we the Democratic Party. This is a Jewish community, and being religious means looking at the world through Jewish eyes, touching it with Jewish fingers, and talking about it with Jewish language. The power of Jewish values is in the truth they bear, and the pursuit of justice is made stronger by our special connection to three thousand years of accumulated wisdom. Take this Sunday as an example: Our community will meet both to clean Jackson Park with a Reverse Tashlich and to inform Hyde Park businesses and employees about immigration rights with the Jewish Council on Urban Affairs. These are only a few of many diverse opportunities to demonstrate the relevance and reach of Jewish religion on public issues.

The prophet Isaiah, at least in this sanctuary, stands for holiness: for building community, for connecting to practice, and for representing Jewish values in our public work. Let’s also be clear that Isaiah does not stand for Jews doing this work alone. Jewish community, and even Jewish religiosity, is not only for Jews. After all, another of our windows quotes Isaiah’s prophetic vision: בֵּית־תְפִלָה יִקָרֵא לְכָל־הָעַמִים , “[My house shall be called] a house of prayer for all nations” (Isa. 56:7). Everyone connected to Jewish community or inspired by Jewish practice or motivated by Jewish values is equally capable of enacting Jewish religiosity. Our religion is not an ethnicity, and it is radically open to all. So, too, is KAM Isaiah Israel.

Friends, we stand in the same room and look at the same windows and reflect on the same religious themes as did our congregational ancestors over a hundred years ago. In some ways, we live in a completely different world. And in some ways, we stand metaphorically side-by-side. Like them, we are heirs to a proud, if flawed, tradition of fighting for justice. Like them, we envision a future that brings us closer and closer to holiness. And like them, we stand as the only generation that can bridge the gap between what was and what might be.

Rabbi Joseph Stolz taught in 1896 what we still believe today:

We want a living Judaism, not a petrified mummy, not a sickly sentimentality, not a vague dreaming spirituality, but that power that sustaineth [us] in the ever-changing events of life. That vigorous life-giving force that makes healthy self-respecting [people], strong characters, loving justice, hating wrong-doing, possessed of a passion to ameliorate the evils of society and to hope for the progress of [humankind].12

May this be the legacy we acknowledge with gratitude and respect when we consider our religious forebears. May it be the future we build for the generations to come, who rely on us for their foundations of faith. And may we stand today as the champions of the enduring values of our congregation: Piety and Love, Peace and Truth, Justice and Holiness.